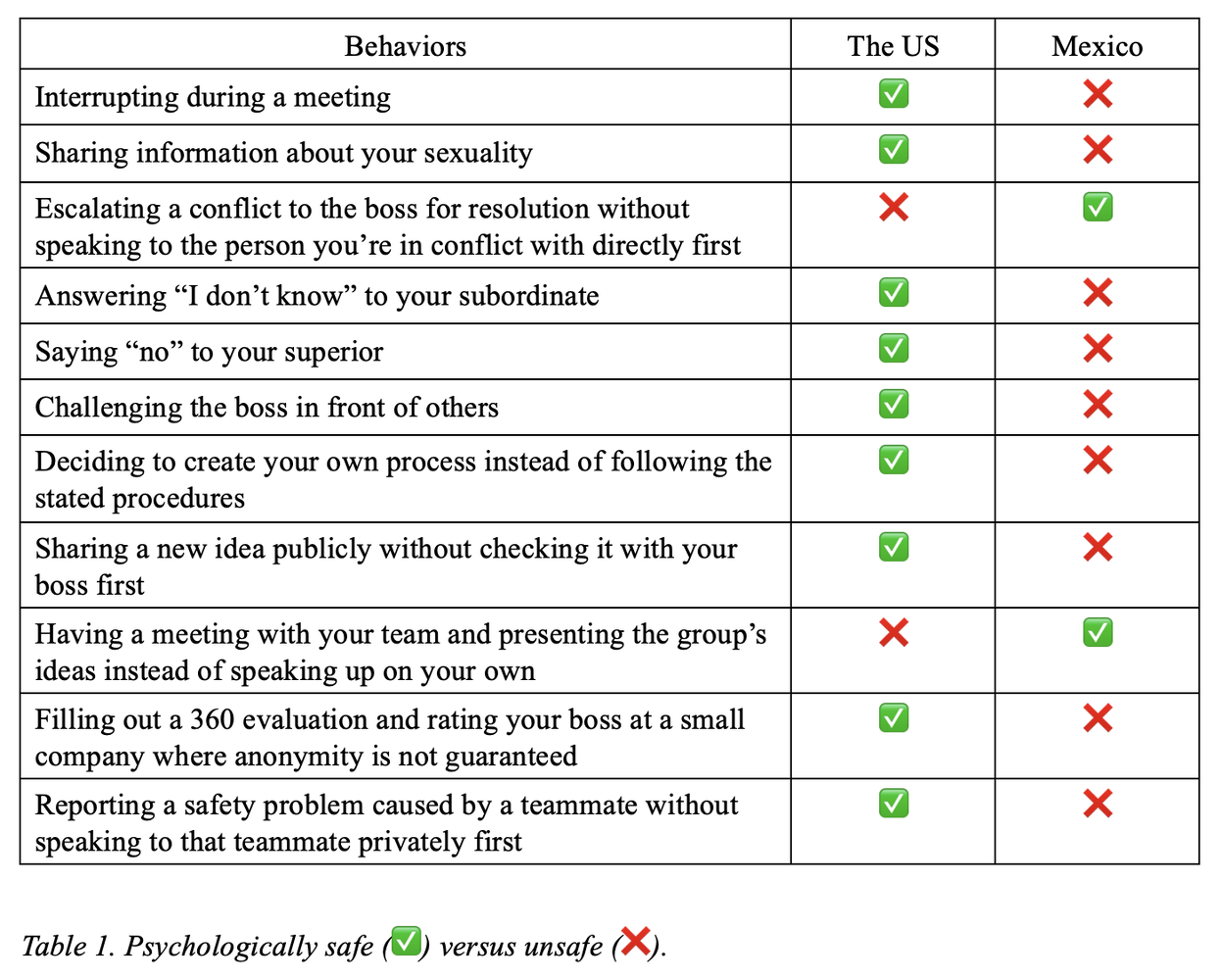

While the two behaviors marked with a red ❌ in the US column could be described as awkward rather than unsafe, the behaviors marked as unsafe in the Mexico column will all cause interpersonal stress at best and job problems (even up to being fired) at worst.

We include the comment about sharing about one’s sexuality deliberately for a very important reason. Different cultures have very distinct ideas about which types of diversity are permissible. When it comes to sexuality, speaking openly about being gay or showing the rainbow flag can lead to fines or incarceration in Russia, where homosexuality was outlawed over a decade ago, the LGBT Movement was banned in November 2023 and designated an extremist group.[10] So sharing your true, authentic self can be more than just psychologically unsafe, it is unsafe in many ways. We recommend extreme caution with the topic of sexuality in general in cross-cultural environments.

In the workplace, making a suggestion on how to proceed with something publicly without running it by the boss first can cause both you and the boss to lose face. For example, if you find out later that what you suggested conflicts with the boss’s preference (after all, it’s not your job to come up with ideas, it’s your job to execute them), you can get in trouble. And 360 evaluations in hierarchical/collectivist cultures can be so intimidating that it can be difficult for subordinates to speak honestly about anything negative, so they tend to write superlative reviews (even of terrible bosses) to stay out of trouble.

What is psychologically safe then?

In hierarchical/collectivist cultures, the people at the top of the hierarchy are supposed to protect those at the bottom and those at the bottom support those at the top by being loyal. Being part of a collective in-group (such as a group of extended family or friends) provides enormous protection in all aspects of life. Inclusion is automatic within your in-groups as long as you take care not to let any “dangerous” personal beliefs or actions harm its reputation. In this way, the in-group has plausible deniability and staunchly protects its members. In-groups also prioritize the interests and reputation of the group over the interests of the individual. Quite often, in-group members know or suspect things about each other regarding sexuality, infidelity, negligence, diversive political opinions, etc, but they don’t turn one another in because they want to preserve the security and harmony of the group.

So, if you are a leader of a team with members from all over the world, remember that speaking up, sharing personal information, saying no to your boss, and other such actions are not necessarily safe things where they live. Efforts to encourage people to share things about themselves that they don’t want to can create situations in which anxiety and stress are created, not relieved. And in certain cultures, even physical violence can be used against those who are suspected of countercultural actions.

How to embrace the spirit of psychological safety programs in other cultures:

Remember that psychological safety isn’t universal. What fosters trust and openness in one culture may create discomfort or even risk in another. The spirit of psychological safety—helping employees feel included, able to learn, contribute, and challenge the status quo—can and should be embraced globally. The key is to adapt the approach at all levels to align with cultural values rather than work against them.

Tips (Do’s and Don’ts) for Adapting Psychological Safety Across Hierarchical and Collectivist Cultures

Inclusion Safety Looks Different in Hierarchical and Collectivist Cultures

✅ Do: Recognize that belonging often comes from group harmony, not individual expression—avoid asking for personal opinions on divisive topics.

✅ Do: Respect hierarchy—Recognize that employees may wait for a direct invitation before contributing.

❌ Don’t: Assume that psychological safety always means public self-expression—privacy can be a form of safety.

❌ Don’t: Expect employees to speak up spontaneously—encourage structured opportunities for input.

Learner Safety Requires a Safe Way to Acknowledge Gaps

✅ Do: Provide structure and preparation—share agendas and expectations in advance so employees feel more comfortable participating.

✅ Do: Encourage vulnerability by modeling it: share about a time you learned something new and how helpful it was to a project’s success

❌ Don’t: Expect employees to admit knowledge gaps publicly—it may harm their credibility.

❌ Don’t: Accuse someone publicly of being wrong or not knowing something. If there is a serious concern, always address it privately.

Contributor Safety Must Align with Group and Hierarchical Norms

✅ Do: Encourage team-based contributions where employees can present ideas as a group rather than individually.

✅ Do: Provide clear role-based expectations for contributions, as hierarchy influences how people engage.

❌ Don’t: Assume that speaking up individually is the best way to contribute—some cultures prioritize collective decision-making.

❌ Don’t: Overlook the importance of hierarchy in decision-making—ensure contributions align with the expected chain of command.

Challenger Safety Can Feel Risky in Hierarchical and Collectivist Cultures

✅ Do: Provide safe avenues for dissent, such as anonymous feedback, structured discussions, or designated intermediaries.

✅ Do: Give explicit permission for challenging the leader and use structured dissent methods—such as Devil’s Advocate roles to allow for non-threatening challenges.

❌ Don’t: Assume silence means agreement—create safe, indirect ways for employees to share their thoughts.

❌ Don’t: Expect immediate, direct responses in meetings—allow time for collective processing before expecting input.

The Bottom Line for Global Leaders

Psychological safety is only truly safe when it aligns with cultural norms. Rather than applying a cut-and-paste approach, you need to build cultural competence—deepen your knowledge, adapt your approach, and actively listen and learn.

Local experts and intercultural consultants are available to help you create an environment where employees feel safe to engage in ways that reflect their values. That’s how you embrace the true spirit of psychological safety—by making it meaningful in every culture.

Reach out to Pia Kähärä at [email protected] or Lisa DeWaard, Ph.D. at [email protected] to schedule a 30-minute no-cost conversation. Subscribe to our email lists to learn more about how to customize your alignment.

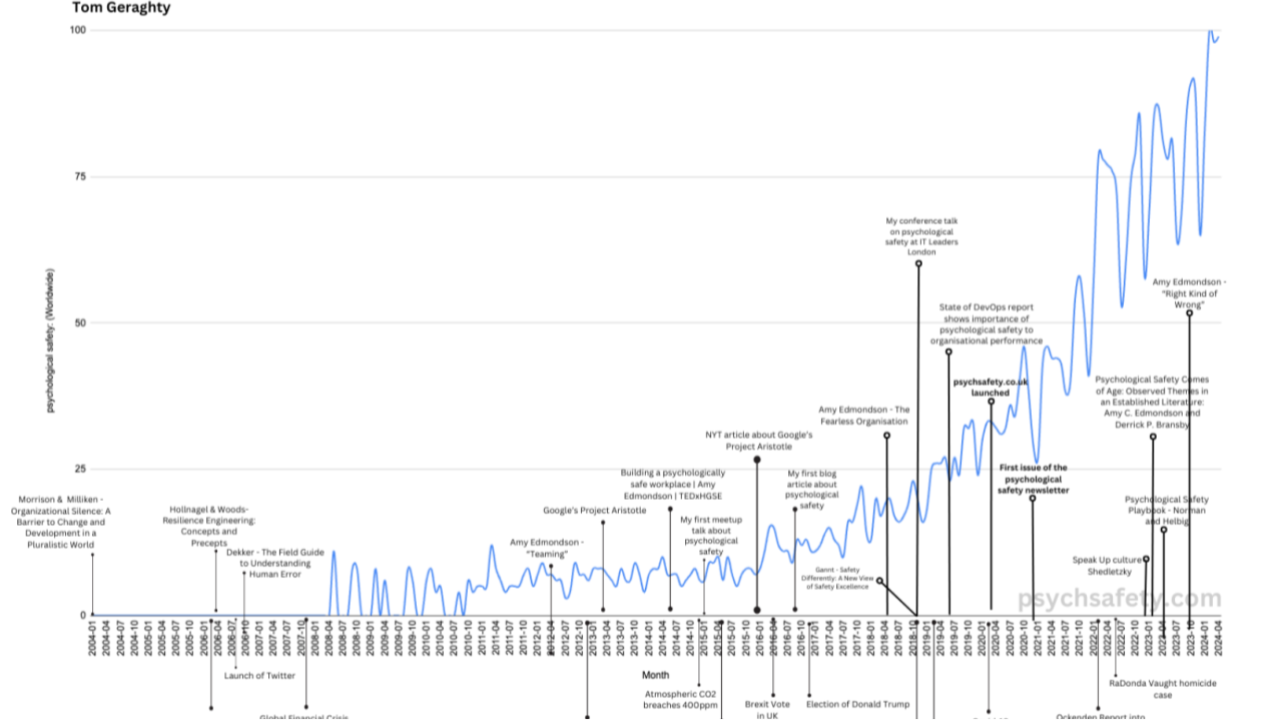

[1] https://psychsafety.com/the-history-of-psychological-safety/

[2] https://www.google.com/books/edition/Teaming/wlnsR9i9b5cC?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover

[3] https://globalcoachgroup.com/googles-project-aristotle/

[4] https://www.leaderfactor.com/learn/psychological-safety-timothy-clark

[5] https://www.theguardian.com/business/2007/may/14/motoring.lifeandhealth

[7] https://www.gallup.com/workplace/247391/fixable-problem-costs-businesses-trillion.aspx

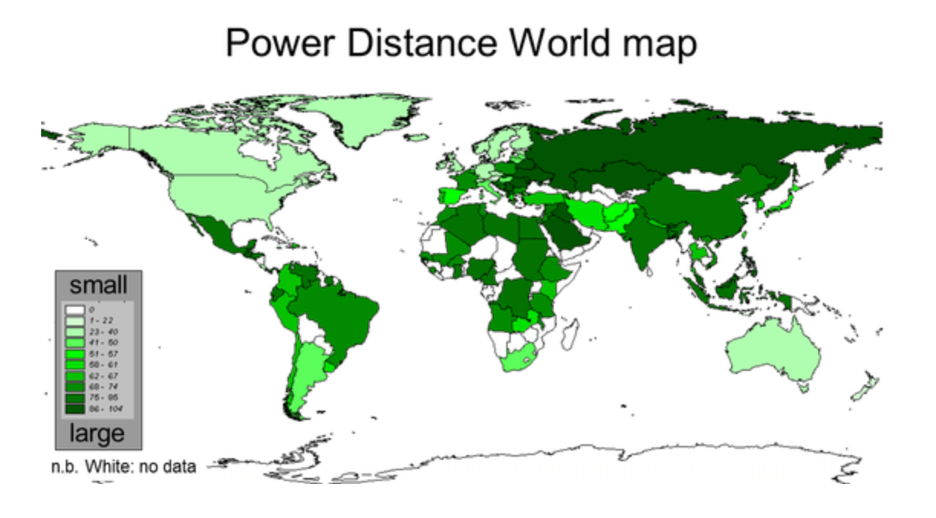

[8] https://geerthofstede.com/culture-geert-hofstede-gert-jan-hofstede/6d-model-of-national-culture/

[9] It must be noted that there is no “better” or “worse” score on any dimension; we simply end up with different looking cultures. Each individual, though, tends to have a strong preference for a particular point on the scale. The greater the difference in the scores on a particular dimension for two countries, the greater the impact of the cultural differences in practice.